Tumour Heterogeneity: A Major Challenge Towards a Successful Cancer Treatment

By Sara Arfan, BSc Biomedical Sciences (Year 3), University of York

Introduction to Tumour Heterogeneity

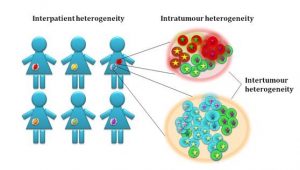

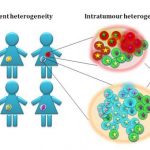

Cancer is thought to evolve from a single ‘stem cell-like’ population which would have acquired a set of driver mutations that are sufficient to initiate the disease. Throughout cancer evolution, the disease becomes more and more heterogeneous as cancer cells acquire different adaptive mutations leading to the development of different subclones within the tumour mass. Not only do these subclones differ in their cytogenetic profiles, but they can also be different at the epigenetics level. Some cancers such as prostate cancer are described to be multi-focal which means that within the same patient, there are multiple different tumours that have evolved independently within the same tissue with different adaptive as well as driver mutations. Another, probably a more obvious layer of tumour heterogeneity, is the tumour variation among patients that are often diagnosed with the ‘same’ cancer. Variations among these patients in terms of their genetic background and overall disease history can very significantly influence their disease progression and treatment outcome.

Conventional Treatments and Therapy Resistance and Relapse

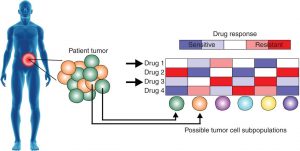

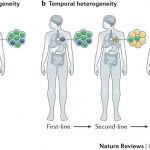

For most cancers, anti-mitotic chemotherapeutic agents and radiation remain the main standard of care treatments. Generally, these work by targeting the highly proliferative cells in the body, which were initially thought to work based on the general consensus that cancer cells are highly proliferative and most cells in the body are terminally differentiated. However, several problems have been recently considered that question the use of this strategy in cancer treatment. Given that the disease is heterogeneous at the cellular level, these types of ‘blunt’ agents might be selecting for subclones within the tumour that are resistant even though these might be the very tiny minority to start with. This is thought to explain the common observation that patients initially responding to the treatment but then a lot of them relapse due to these treatment resistant subclones being the dominant cells within the tumour mass. In addition, other chemotherapeutic agents that target specific pathways which are upregulated in cancer may be inducing resistance in some cellular subclones, as they are thought to push the cells towards finding a ‘salvage pathway’ that complements that blocked with the treatment.

Current Trends in Cancer Research

Cancer research has long considered cancer as a homogeneous mass of fast-growing cells, which has been disadvantageous in terms of the development of effective cancer treatments. On the other hand, the first annotation of the human genome in 2001 followed by advances in sequencing technologies leading to the development of next-generation sequencing which was first introduced in 2013, has largely influenced the field of cancer and biomedical research in general. Since then, there has been a large interest in how mutations or genome variations among individuals map onto disease phenotypes and how that can be exploited in terms of treatment. Cancer is not an exception and personalised cancer medicine has already shown to be promising in some cancer treatments. However, this only covers a small number of cancers and still faces several problems regarding its practicality. Cancer research groups are now looking at single-cell sequencing of tumour biopsies and analysis of the individual subclones of cells, which holds the promise for more potent treatment approaches in the future.

References